For decades, the airline reservation was the focal point for every automated travel itinerary. Despite considerable internet-enabled innovation, it still largely remains that way today. Now the International Airline Traffic Association (IATA) has embarked on it ambitious “New Distribution Capability” (NDC) initiative, with the stated objective to “define a messaging standard that will enable retailing opportunities.”

Airlines want full control over their passengers. Once inside their brains, they can trigger brand preference cues that dictate specific behaviors

Image Credit: driph (cc/flickr)

Calling this initiative self-absorbed is a gross understatement. The page content of the NDC homepage mentions neither “travelers” nor “passengers.” The NDC blog posts discuss passengers, but inevitably within the context of cost-recovery, yield and revenue optimization through the sale of unbundled services.

There are plenty of references to offering choice and customization (nothing wrong with that) but there is one term that is auspicious in its absence: “satisfaction.” Discussion of how NDC can better integrate air travel with the rest of the travel industry to enhance the end-to-end experience is woefully absent.

How many travelers take trips with the primary objective of experiencing an inflight experience on a commercial aircraft? If you find one, double check to see if they are actually paying for their own tickets. Sadly, that pursuit largely died with the demise of the Concorde, although a few aviation geeks have been quite excited about the 787, battery problems notwithstanding.

The driving motivation behind the NDC initiative is structurally changing two business models and exercising market control. Unfortunately, it has very little to do with technology.

The first business model is facilitating the sale of a growing menu of unbundled services. While carriers may argue that this initiative will offer the passenger superior choice, these options rarely create consumer value – most services were formerly available for free.

The ancillary services have been unbundled primarily to generate high margin incremental profit, not to empower consumers. Painfully little attention has been dedicated to improving passenger comfort, satisfying consumer demand or enhancing the travel experience.

The second business model under attack is the distribution supply and value chain. Traditionally, suppliers paid distribution channel costs, with intermediaries providing a revenue share upstream to the travel sellers engaging with consumers.

Airlines successfully zeroed out travel agency commissions a decade ago, forcing most brick & mortar travel agents to shift to transaction fees. The major Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) were holdouts due to either ownership with vested interests in Global Distribution Systems (GDS), or to maintain the GDS “productivity bonus” fees as one scarce source of air booking revenue.

With little incentive to continue supporting the traditional distribution processes, the ability for consumers to purchase unbundled services became largely an exclusive feature of the airline’s own website. Share shift for leisure bookings from expensive intermediary to lower cost direct channels was neither an unwelcome nor unanticipated result.

However, with neither a viable business model nor distribution capability to efficiently transact sales, technology development for ancillary services through third parties never took off. Lots of finger pointing resulted, but the reality is that interfaces don’t happen unless suppliers are fully invested in their success.

So now, the burning question is whether NDC will streamline airline reservation processing, enable improved personalization and help increase both demand for, and conversion of, traveler intent into incremental trips?

Not to jump to conclusions, but given its current structure, that is highly unlikely.

First, a History Lesson

It all started with a few airlines creating Central Reservation Systems (CRS) that evolved into the current GDS’.

The carriers wielded GDS agreements like weapons – resulting in governmental regulation of fairness rules to avoid anti-competitive behavior toward other airlines and consumers.

Worse yet, little consideration was given to interrelationships with hotels other components within the travel ecosystem. The hotel industry bore the brunt of onerous GDS agreement terms that dictated hotel groups must react to technical changes based on as little as 30 days notice.

After the hoteliers fundamental needs were ignored by the airlines for several years, in 1989, the environment became so untenable that more than a dozen bitterly competitive hotel groups banded together to form “The Hotel Industry Switch Company” (THISCO.) They created what is now known as the Pegasus switch to better manage transactional GDS interfaces and create opportunities to bypass the GDS infrastructure.

However, hotel booking innovation through the GDS channel remained stifled by insufficient planning or foresight by the air carriers even as the Internet-age dawned. In 1996, 2/3 of GDS hotel bookings were still made through “passive segments;” the unstructured, text-based notes that were used by travel agents to record hotel itinerary information that had been booked through alternate channels, like telephone, email or fax.

This underscored their obliviousness to both lodging industry needs and a lucrative business opportunity (no revenue stream was associated with the passive itinerary segments) all that mattered were the GDS-processed airline bookings. And their revenues reflected that strategy – over $2 billion in revenue from airline bookings and under $50 million for hotel bookings at one leading GDS.

The root of the problem was systemic. A startling reality was that to enhance hotel descriptions in a GDS, it was necessary to extend the BAS – the Basic Air Segment. That’s correct, even within the last decade, the square peg of hotel information, relied upon by millions through travel agents and online travel websites, was hammered into into the round hole of a data structure designed to describe an airline product.

Over the following fifteen years, as most GDS hotel databases have progressively been migrated off of the old TPF frameworks into relational databases or accessed interactively, the arrogance and self-absorption of the airline industry has again begun to rear its ugly head.

But back in 1999, a consortium of leading air carriers, working in concert with leaders from other travel verticals, established the non-profit OpenTravel Alliance to create a standard XML schema to facilitate the communication of traveler information between trading partners and across the industry.

Most importantly, this was done as an industry-wide initiative involving a wide variety of players within the travel industry.

It should be noted that the original OpenTravel XML messaging specification (Version 1.0 was published in July 2000) represented a remarkable degree of industry collaboration and is largely responsible for the vast majority of interfacing activity that has enabled everything from dynamic packaging to mobile apps. The effort involved an interoperability committee responsible for integrating the work contributed by working groups comprised of airlines, hotel, car rental, trade associations, GDS, technology providers and content publishers.

The OpenTravel spec was not perfect, but it allowed the industry to take huge steps forward by helping all involved smoothly exchange information. Most data elements were made optional so the specification would not unduly disenfranchise groups that had to navigate existing technological hurdles or new players developing innovations that reimagined the smooth exchange of information.

The OpenTravel Alliance established specifications have been continually enhanced over the years.

In July 2008, Graham Wareham, General Manager Product Distribution for Air Canada highlighted the important role OpenTravel had played in the industry and its importance moving forward:

“Air Canada believes open XML standards are critical to the technical advancement of airline distribution. Because OpenTravel’s standards are so widely adopted, we can now forge new commercial partnerships with enhanced distribution of our products and services. The ability to generate ancillary revenues through channels beyond our own website is key to our distribution strategy. The project Air Canada is leading will address the ability to offer additional services and discount options to the air traveler at time of reservation and to properly display these options at various points of a booking process.”

Then something changed. Some key members of the OpenTravel airline working group slowly curtailed their level of participation. While the airline industry was focused on aggressively unbundling its services to drive ancillary revenue streams, there was not comparable engagement on developing open industry standards to facilitate the broad distribution of these new services.

In mid-2010 the reason for decreased airline contributions became apparent – The airline-exclusive Open AXIS initiative was announced by an influential group of five airlines and two other organizations: Farelogix and Airline Tariff Publishing Company (ATPCO). Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC) joined the Open AXIS board three days following inception.

The XML schema adopted by Open AXIS was not created by the member carriers, it was contributed by Farelogix, a for-profit corporation with a reputation for antagonistic relationships with travel intermediaries.

But here the plot thickens. Open AXIS was not successful in creating a following among non-founding airlines. While its ranks ultimately included 50 organizations, all additional participants were technology providers, not air carriers. Open AXIS had failed to gain traction within the airline industry.

Two and one-half years later, in January 2013, ATPCO purchased Open AXIS, reportedly for the sum of $1.00 and the assumption of debt that some parties estimated at six figures.

February 2013 then brought a decision by IATA’s Passenger Service Group to utilize the Open AXIS Schema as the foundation for IATA’s New Distribution Capability.

In May 2013, IATA assumed the license for the Open AXIS schema from ATPCO, which according to the press release, made “IATA the custodian of the Open AXIS XML schema, with full governance over schema evolution, including further development, maintenance and standardization efforts.”

Suddenly, the successful, industry-wide perspective nurtured by OpenTravel to develop travel industry XML interface standards was subverted, with control over airline standards now locked inside a gated airline community.

So much for the history lesson.

FLXing some Airline Muscle

Farelogix CEO Jim Davidson, concisely describes the FLX Airline Commerce Gateway:

“The Gateway is an industry breakthrough as it’s the first solution to integrate and optimize industry leading distribution technology engines into a single, “out-of-the-box” solution that can serve all airline sales outlets, including the fast growing mobile channel.”

In essence, the platform is designed to provide a one size fits all solution for the airline industry. Within the context of Open AXIS, when compared with the open framework for seamless industry-wide communication developed by OpenTravel, this represents a radical departure from standards initiative to commercial venture.

The primary OpenTravel objective of open communication had morphed into the Open AXIS objective of iron fisted control.

Thinking this assumption of the desire for megalomaniacal control may be an overreaction? Check out the splash screen video that automatically runs when the Farelogix website is opened:

To quote the preamble here: “What happens when you don’t have control? You miss opportunities. You let others take the lead. The best way to lose, is to lose control.” It continues with “where every touchpoint represents an opportunity to compete for, and to win, a customer’s loyal business, are you ready to create and control your own offers?”

The three main goals of the platform are expressed in the video:

- Increase Revenue per Passenger

- Improve Customer Retention (by growing successful rewards and redemption programs)

- Know How to Best Recover a Customer After a Negative Experience

Sadly, there is no mention of better meeting customer needs, anticipating/eliminating those negative airline experiences, or creating a smoother end-to-end experience for the customer across their full travel itinerary.

The FLX Gateway is powered by three engines that operate “exclusively under the airlines control”:

- Pricing

- Merchandising

- Distribution Business Rules

It also stresses the provision of a single API, consistent with IATA’s New Distribution Capability workflows. This is logical, since Farelogix created them.

The irony is that for those who were not initially involved with the development of the Farelogix/Open AXIS/ATPCO/IATA NDC “solution” there is no control, so the video fundamentally explains why everyone else should be wary of joining this initiative and its small band of airlines who are attempting to exert “control” over the rest of the travel industry.

Even more ironic is the fact that four of the five founding carriers were responsible for creating the GDS decades earlier – entities that the carriers now claim have too much control over the industry. That was no accident – that was the intention of those same carriers all those years ago, and using the leading technologies of the day, they were largely successful.

Now, since having divested their majority shares of the GDS, the airlines seemingly want to start anew to establish a modern technology platform where they can again establish control. Same players, same motivations, new technology.

Jim Davidson & Farelogix are not evil, they are just opportunistic. To the point that the lines between an open industry standard and a commercial product have been blurred. The airline industry has allowed it to happen, because frankly, they can.

The main problem is that in the travel industry, as has been proven out by the GDS experience, one size definitely does not fit all, and a single “solution” inhibits innovation.

I strongly support supplier-centric platforms that level the playing field with inefficient intermediaries that absorb potential consumer benefit as gross margin. Over a decade ago, I was on the team that created Neat Group, the first travel dynamic packaging platform that provided travel suppliers with complete control over pricing and distribution rules.

Pricing and distribution rules aren’t the problem here.

The core issue is suppliers possessing the market power to usurp complete control over the merchandising aspects of a sales process. It’s the merchandising (demand side) of the equation where the airlines are now focusing their efforts.

In short, travel suppliers, particularly oligopolistic airlines, may not be the best suited to decide the ideal methods to merchandise their products to customers – especially if those services must be integrated into a traveler’s end-to-end trip itinerary.

Following are two vivid examples:

Oren Etzioni, University of Washington Computer Science Professor and Artificial Intelligence pioneer, introduced Farecast at the 2005 PhoCusWright Conference, where I stood at the back of the room amongst a group of airline executives.

Oren was applying Big Data concepts to predict airline pricing long before Big Data became the popular buzzword it is today. It was a compelling presentation and Farecast was later acquired by Microsoft to become the core differentiating feature of Bing Travel.

During that presentation, however, the airline execs were laughing at him, with remarks generally ranging between “he’s delusional – he doesn’t know the airline industry” and “if it does work, we’ll just figure out a way to break it.”

I heard similar sentiments for years surrounding the time bar format in ITA Software’s Matrix Airfare Search. Having successfully used the ITA demo site to plan my travel for years, it was interesting that airlines (and a lot of OTAs) regarded the time bars as a purely academic model that was too complex for use by the traveling public.

Years later, Adam Goldstein, 23 years old and a week out of MIT, created Hipmunk, leveraging the time bar format to remove the “agony” from booking airline tickets. Everyone I know who uses Hipmunk loves it. Hi[pmunk even won the Webby Award this year for Best Travel Website (although Adam still needs to figure out a way to charm Southwest Airlines into providing access to fares and inventory…)

Arguably, these two merchandising innovations, that went largely unsupported by the airline establishment, represent perhaps the most significant consumer-facing merchandising enhancements within the airline industry over the past decade. All indications are that letting airlines exclusively decide how they are to be sold will not move the industry forward.

A New Air Travel Control Tower

Innovation typically means disruption, and that is the primary factor that the major carriers, and IATA, are trying to “manage” through the establishment of NDC.

What is required is a flexible, structured framework for this information to be easily communicated between airlines, consumers and all their inter-related trading partners.

Broad participation in the standards creation process, as well as open review by those inter-related trading partners is particularly important. That is what made the OpenTravel Alliance specifications such a success.

Due to the adoption of the commercial Farelogix XML Schema, and the relatively closed circle of major carriers that have stakes in Open AXIS, ATPCO, ARC & IATA, the prospect of open review and enhancement is somewhat suspect.

In late 2012, IATA filed Resolution 787 with the United States Department of Transportation. It proposes the establishment of a single Dynamic Airline Shopping engine Application Programme Interface (DAS API) based on IATA NDC XML messages that will control all airline passenger interactions.

IATA’s description is unambiguous:

“A standard process is required for airlines to create their own product offer within their own systems (i.e. assemble fares, schedules and availability – all in one transaction) which will be provided directly by and owned by the airline.”

The DAS API serves as bookends to an “Interactive Exchange” that controls the rules, authentication and distribution governing of access to airline availability, fares and schedules.

Not only does this description try to make one size fit all, but it also closely parallels the design of the Farelogix FLX Airline Commerce Gateway – and not by coincidence.

But how could a commercial application suddenly be transformed into a legally binding process that impacts the global airline industry? Who are the decision makers who would allow such a thing to occur?

Even Google, Microsoft & Yahoo collaborated on the open schema.org specification that helps create context to help everyone search more efficiently across the Semantic Web.

Like in baseball, you can’t tell the players without a program. The only difference here is that when comparing a list of airline industry decision makers and baseball teams, the baseball teams have much larger rosters.

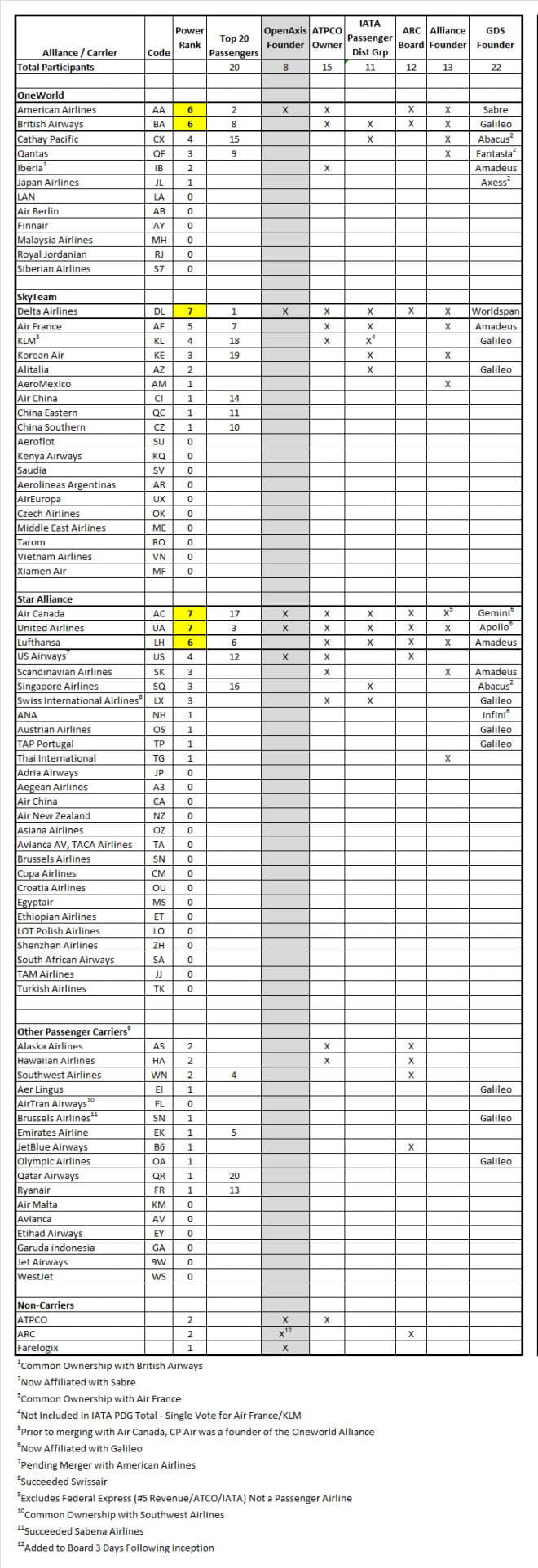

The chart below illustrates the highly incestuous relationships that exist between the world’s largest airlines, ATPCO ownership, the Airlines Reporting Corporation Board, IATA’s Passenger Distribution Group, airline alliance founders, the original GDS founders and Open AXIS founders.

A Power Rank was established as a measure of the dominance any single carrier may have over these various groups. The Power Rank tallied the number of these participation attributes for each airline.

The World’s Leading Airlines – At least in the distribution world. Mostly because they dominate passenger traffic, ATPCO, ARC, founded GDS’, alliances and Open Axis, plus the IATA Distribution Group.

Take careful note of the Power Rank scores for the five Open AXIS founders and their primary partners within the three airline alliances:

OneWorld

- American – 6/7 (Founder)

- British Airways – 6/7

SkyTeam

- Delta – 7/7 (Founder)

- Air France – 5/7

Star Alliance

- Air Canada – 7/7 (Founder)

- United – 7/7 (Founder)

- Lufthansa – 6/7

- US Airways – 4/7 (Founder)

Four of the five Open AXIS airline founders scored six or higher (out of seven) on the Power Rank scale. The highest Power Rank for a non-alliance member was a two, scored by Southwest Airlines, the 4th largest in the world, and two others. Emirates, the world’s 5th largest airline only scored a 1 for Power Rank.

A mere three of the 75 airlines listed managed a Power Rank of 4, including remaining Open AXIS founder US Airways, KLM (under common ownership with Air France) and Cathay Pacific. Each is also affiliated with a different airline alliance.

NOTE: The original version of the article flagged US Airways as having a Power Rank of 5 – due to their founding of the COvia GDS in the 1990’s. However, in the interest of being conservative, the Power Rank was later reduced to a 4 so only 1st generation GDS founders would be recognized as leaders. This is now somewhat a moot point given US Airways pending merger with American Airlines.

The eight airlines listed above dominate the global airline industry, and in this case, its newly minted distribution standards, through their ownership in the bodies that govern the global airline industry.

Democracy in Action

Of course, with such an important decision as determining the best technological approach to establish an airline industry standard, the best method would be to directly compare the various options based on predefined criteria. And that was exactly what the IATA Passenger Distribution Group (PDG) did.

Seventy-three empirical criteria were defined for the evaluation of the best schema for the NDC initiative. Both the OpenTravel and Open AXIS schemas were presented.

Interestingly, the individual responsible for pitching the Open AXIS schema to the committee apparently served dual roles as the head of product development for Open Axis and as the vice president of merchandising solutions for Farelogix.

The final outcome of the evaluation?

The OpenTravel schema narrowly edged out the Open Axis schema by a score of 96% to 48% for an overall score, and 100% versus 56% for the subset of merchandising messages.

The IATA Passenger Distribution Group subsequently voted. Two independent sources confirmed “The Open AXIS schema was approved by a 10-1 vote, despite having received lower scores in IATA’s evaluation process than the OpenTravel Alliance’s schema.”

Understanding that a) three of the eleven voting members represented Open AXIS founders, and b) all remaining members participate in airline alliances founded by those Open AXIS founders, would provide some important context for political dynamics of the vote.

The decision of the IATA Passenger Services Group was not based on the technology, the central issue driving the decision was governance. The group elected to go with inferior technology, as measured by their own standards, so they could wield full control over the specification.

That makes IATA’s pitch to the US Department of Transportation to support Resolution 787 as a means to implement a new “open” technology ring a bit disingenuous.

This process should give any external group interested in having its innovative or disruptive contributions to enhance the IATA NDC specification justifiable cause for concern. At least in the current climate, any proposal that potentially reduces airline control over pricing, distribution or merchandising, regardless of its benefit to improve travel industry efficiency or create consumer benefit, will face long odds at being incorporated into the standards.

There are many constituencies that can benefit from truly open standards to engage with travel products – Consumers, corporations, travel agencies, wholesalers, GDS’, search engines, other travel suppliers and other airlines. Unfortunately in the closed world of NDC, none of those other groups possesses any modicum of control – the original Open AXIS airline partners, Farelogix and IATA/ATPCO apparently call the shots.

This sort of political environment has no business influencing travel industry data exchange standards.

A similar scenario for lodging might be Airbnb proposing new schema extensions to support peer to peer short term rentals. If the standards were controlled by the hotel industry, the proposal would never be considered – based purely on political agendas. Within the framework of the OpenTravel Alliance however, the hotel working group might not be overly pleased, but the specification expansion could move forward without negating the existing hotel schema and at least leveling the distribution playing field for all participants.

If a similar scenario existed in the financial services industry, for example, if credit card companies controlled all aspects of the pricing, distribution and merchandising of settlement processes, any highly innovative and disruptive groups like Square or Dwolla would never be permitted to transact with a merchant. Fortunately, neither of these fictional scenarios are the case.

Reeling in the Years

The real tragedy is that with the major carriers going all-in on the Farelogix XML schema, future enhancements in the area of airline search and booking will likely be sidelined as the airline industry wrestles for total control of the air traveler’s itinerary. Open AXIS failed once, but now it’s round two; the stakes have been raised, but the players and underlying technology are unchanged.

I fall back on the famed Rita Mae Brown (sorry – not Einstein, Benjamin Franklin or Mark Twain) quote: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”

It is within the realm of possibility that IATA could open up NDC and work to efficiently integrate it into the Air specifications of the OpenTravel Alliance, but that is highly doubtful. While not taking that route simply looks crazy to me, doing so would require some release of control – and as the Farelogix video reminds us, loss of control is apparently tantamount to failure.

To a great extent, the airline industry has turned its back on the larger travel industry in an effort to transform business models and establish dominant control over all aspects of its distribution channels. These standards don’t just impact airlines – they impact all sellers of travel and the patrons of hotels, car rental and activities that happen to travel by plane to their destination.

It looks a lot like history repeating itself when the airlines dominated travel distribution through the GDS. Control was exerted. Innovation suffered. Traveler satisfaction plunged.

In an era of unprecedented technological innovation, facilitated by the democratization of information, development of open systems and guided by cooperatively developed industry standards, such a closed structure and approach is repugnant.

Hopefully the mistakes of the past will not be repeated. But then again, seeing the same thing happen again and expecting a different outcome would be insane…